That sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it? Well, I’m here to tell you that it’s not only possible, but relatively easy to do and can even be done with no special parts (although using some special parts can definitely improve the performance). There is a catch of course, namely that without having a source of electricity, the signal you use won’t be very loud, and you’ll have to listen via ear phones (and a particular type at that – more later).

The simplest of radios can be built with simple wire, a crystal or equivalent, and an earphone. I’ve built this kind of radio, and while it works – which seems miraculous enough – its performance is less than spectacular. It only picks up the very strongest of AM stations, and it picks them all up at once. Fortunately, we can do much better by adding more wire in the correct configuration, a tunable capacitor or two, and a handful of other innovations.

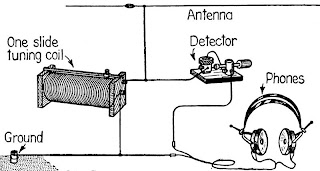

Simplest Possible Radio

(Courtesy of Wikipedia)

More specific and detailed construction information can be found on the Internet

Now don’t get me wrong. A crystal radio is a poor substitute for even the cheapest modern AM/FM radio in terms of ease of use, portability, and sound fidelity. If you have one, I wouldn’t throw it away simply because you can now make you own. I would however, still build one, simply because you can. Why? Because doing so is a step toward independence. It’s one less chain binding you to the culture of external dependence.

It’s also a good example to show that technology itself isn’t the enemy. In its proper place, technology can be liberating and empowering. As I’ve said many times, technology is supposed to work for human, humans aren’t supposed to work for technology and that includes the self and externally imposed slavery of having to work to acquire it. The crystal radio is enabling because it provides a path for those who actually need a radio to acquire one without undue expense of resources.

A historical example of the utility of the crystal radio can be found in World War II. GI’s in the European Theater listened to radios for both news and morale. Clever German scientists and engineers discovered a way to detect the presence of US troops by the signal generated in the local oscillator of their portable radios. The radios were consequently banned; leaving the GI’s to do without a vital link to the outside world. Clever soldiers began building crystal radios with materials they had on hand, restoring the link. The radios they built were crystal sets, which don’t have a local oscillator, and thus did not give away their position.

Part of what makes the foxhole radios so amazing from a technical perspective, is that they didn’t actually have a crystal. The detector (the role the crystal plays) was created by holding a razorblade to a flame and using the scorch-mark as a primitive semi-conductor – in effect, a diode. That is sheer, liberating genius, and even if it didn’t play a major role, anything that kept the morale of our soldiers up certainly helped the Allies win the war.

There is a fly in the ointment to all of this, however. These crystal radios are restricted to analog signals. The current push toward digital broadcast will make them obsolete. This, strictly speaking, doesn’t mean that you can’t still build your own radios, but it does mean that you must have an external power source because the electronics needed to decode a digital signal consume power.

I work in the field of technology and communications, and although it hasn’t really been a career enhancing position, I’ve long been opposed to the digitalization of media and communications. My opposition is based on the principle of accessibility. An analog signal is accessible in a much wider array of circumstances than a digital signal, albeit at the expense of quality. The human ear (and eye) can listen or see around a great deal of noise such as static, artifacts, or other interference. A digital signal is either perfect or unavailable, due to the nature of the decoding the ones and zeros that make up a digital signal, and in marginal conditions digital signals fail long before analog systems. They are also far more dependent on stable power conditions. (There are a few exceptions to this statement, predominantly found in the world of HAM radio, which I’ll discuss in future posts, but these aren’t actually ‘digital’ modes of communications – a CW signal (morse code) for example, is either ‘on’ or ‘off’, but the actual information isn’t directly contained in the ‘on’ or ‘off’ state, and the human ear can decode weak CW signals through a process of inference).

The move to digital communications and media is driven by the pursuit of money. Manufacturers want to sell you the equipment needed to decode the equipment, and thus the encoding schemes are often proprietary for the express purpose of limiting access to customers. Media content providers encrypt their products to limit the ways in which you use your purchases. In principle this is fair enough, and everyone deserves to be rewarded fairly for the fruits of their labors. In practice though, they are accomplishing these goals through the use of the common airwaves, which they hold only through public trust – part of that trust is that they provide critical information and make it freely available. The transition of the public airwaves to proprietary formats is, in my opinion, a violation of that trust.